|

| Contraction in China's Manufacturing |

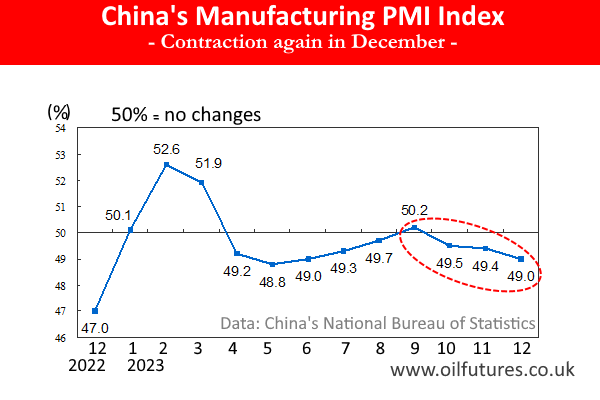

The latest data released by China's National Bureau of Statistics clearly shows that the the activities of the global manufacturing powers house, China, was down again in December, 2023.

In fact, it has lost 0.4% points, from 49.4% in November to 49% in December. The significant index has been on a downward trend since September.

The Manufacturing PMI of China is a barometer that represents China's manufacturing activity in a given month: the authorities survey the manufacturing managers in the vast country to gauge the activities at first hand; its threshold is 50% that indicates no changes; if it is above 50%, as happened in September, it is an expansion of the activity; on the other hand, any number below 50% is a contraction.

With the latest data, China admitted explicitly that its manufacturing activity has contracted in the past four months. The admission has already cast a long shadow over the global energy sector, as the Chinese factories use up energy in all forms, perceived as good, bad and anything that falls in between, to power the vast network. while being the world's second largest consumer of fossil fuels.

Making matters more alarming, even in a busy month before the Christmas, there has not been a heightened manufacturing activity in China. when the goods are in heavy demand.

Therefore, not only does the seemingly simple metric indicate where the appetite of China stands on the scale of global energy consumption, but also provides the energy market watchers with valuable insights.

When the PMI rises above the threshold, 50%, for instance, factories hum while production lines roll; as a result, China uses up vast amount of coal to run boilers, huge volumes of gas to produce electricity and millions of barrels of oil to run machinery while all rise in tandem.

As an inevitable consequence, the energy consumption ripple through the energy markets that results in the rise in commodity prices and tightening of the supply. For instance, in 2021, the PMI surged and China's heightened activity led to a shortage of global coal supply that ended up causing an alarming surge in global energy prices.

By contrast, the value of PMI below 50%, indicates a contraction in manufacturing activity and by extension, a slowing demand for fuels. The failure of oil prices to rise above $80 in a sustainable manner for the past few months, just shows the strongly-positive correlation of the two, despite the misplaced optimism of some producers who believe otherwise.

Investors were right, after all: they, at first, pinned their hopes on China's estimated manufacturing boom for months, only to get disappointed when things did not turn out as widely anticipated; fortunately, they did not throw caution to the wind, while losing vast sums of money; China's reluctance, meanwhile, to admit openly that it was the case hardly helped piercing the canopy of melancholy that looms over the energy markets at present.

Beyond the binary, however, the relationship between the China's PMI and the global energy demand may be a bit more complex; there is much more than meets the eye.

A drop in demand for the cheaper goods from China's trading partners, for instance, can dampen the production despite the PMI remaining high. On the other hand, if factories manage to operate at low capacity to meet the sales obligations, it may not lead to a sharp rise in demand for energy.

Besides, China's tendency to embracing energy-efficient technologies may perhaps decouple the existing strong connection between its Manufacturing PMI and global energy demand, leaving it partially redundant in the years to come.

China may even emulate the diminishing energy foot print of the lighter industries such as pharmaceuticals and electronics, while compelling energy-intense heavy industries such as steel and cement to follow suit. A shift of this kind will mitigate the impact on energy demand by the current, notoriously fluctuating PMI.

All in all, at present, China's manufacturing activity, its genuine desire to energy transition and the healthy global demand for its goods remain the major factors that can change the not-so-distant horizon of the global energy landscape. An investor who navigates the complexities of the energy market while ignoring Chinese factor is like a Uber driver who lost his GPS before making the food delivery to a long-established hungry customer in his urgent need.