|

| Oil prices in 2023 |

With the oil price rally that we saw on Monday being dubbed as one of the shortest of its kind, Saudi Arabia, the largest crude oil exporter in the world, has been left reeling from yet another shock from the unpredictable behaviour of the commodity markets.

As of 13:00 GMT on Wednesday, the prices of WTI and Brent stood at $72.48 and $77.01 respectively.

The Kingdom did turn towards the most rudimental pillar of economics out of desperation to shore up the dwindling oil prices - demand and supply; it hoped that by cutting down on the latter, it would increase the former and thereby, of course, the prices - and then its revenues in that order.

With that hope, Saudi Arabia announced a voluntary production cut of over 1 million barrels at an unusually contentious OPEC+ meeting on Sunday. The de facto leader of the OPEC+, Saudi Arabia, always had a messianic presence in the organization since its inception in 1960.

In its heyday, for instance, Sheikh Yamani, the former Saudi petroleum minister, had such an influence in the oil markets that he could literally bring the prices of oil up and down just by moving his eyelids in the same directions, as every word he used to utter was under intense scrutiny by the markets; he used to do it even without being a member of the Saudi royal family - just an educated, no-non-sense commoner.

Judging by the difficulties that the Saudis encountered at the OPEC+ meeting on Sunday in its endeavour for oil production cuts, it is clear that the influence of the Kingdom in the group appears to be on the wane.

When Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, Saudi energy minister, announced that the voluntary cuts of over 1 million barrels per day at the weekend, understandably, the markets reacted favourably on Monday, the next day, quite feebly at first, only to fall back to where it had been up until then.

By evening on Tuesday, however, the prices of oil have fallen back to the level they had been at for weeks, dealing a hammer blow to the short-term Saudi strategy that appeared to have stemmed from an axis of strong emotions rather than that of responses to evolving market trends.

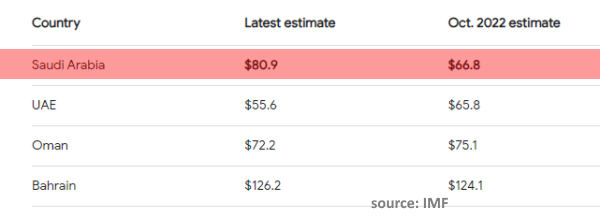

Recently, the IMF published the data highlighting the break-even prices for the major oil producers in the world: it was just above $80.90 for Saudi Arabia; the price of Brent at present is a way below that; you do not have to be a rocket scientist to gauge the direct impact on Saudi finances, if the status quo remains as it is. In this context, Saudi frustration - or even apprehension - is perfectly understandable.

In 2021 and 2022, the corresponding break-even prices had been $75 and $67 respectively. It means, the estimated value for 2023 has gone up steeply, leaving the Kingdom at a very difficult position.

The way break-even prices of each producer has risen in recent years clearly shows that the latter is not immune to inflationary pressure either.

Having been committed to quite a few mega-projects aiming at a post-oil era, the Saudis need money for fulfilling the grand ambition. Since its main income comes from oil, selling the very commodity way below the break-even prices has pushed the Kingdom to the wall.

|

| Breakeven prices of oil - 2023 |

In addition, it has to address the growing needs of a relatively young populace in order to nip the potential for dissension in the bud ; over 63% of its 32.2 million inhabitants are below the age of 30 years.

When Prince Abdulazis bin Salman, the Saudi oil minister and the half-brother of Prince Mohammed bin Salman, threatened the short-sellers last week against the 'market manipulation' and vowed a proportional response, it reflected the gravity of the issue faced by the Kingdom.

The anticipated response from the Saudis against the short-sellers, however, at the latest OPEC+ meeting on June 4, was more of an individual move rather than a collective strategy; Saudi Arabia announced a voluntary production cut of 1 million barrels per day - bpd - whereas others prefer sticking to existing quota of production cuts.

In short, the de facto leader of the OPEC+, Saudi Arabia, much to its dismay, appeared to have found out that it was not easy to call the shots anymore in the organization.

As far as the other members are concerned, including Russia, they just want to sell oil and make money; it is a case of making hay while the Sun shines; they may have realized that the production cuts did not necessarily mean an upward movement of the prices of oil - based on their very own, recent experiences.

The members of the OPEC+, who are reluctant to go for more production cuts, appear to be aware of the current state of the global economy, which is far from rosy; they are aware of the destructive role played by the high energy prices in pushing the world to the brink, something that the Saudis had overlooked in order to address its own revenue concerns.

As for the Saudis, the production cuts mean the loss of revenue in direct proportion. As a result, Saudi Arabia has been compelled to increase the price of oil for its most loyal customer base for decades, Asia.

This will result in them turning towards Russia for their energy needs. China and India, the world's second and third largest consumer of oil respectively, for instance, have already embarked on a buying spree, knowing very well that the threat of international sanctions is manageable, thanks to their growing political influence on the global stage.

If the price of oil from the Middle East goes up, they will keep buying more oil from Russia and the rest of Asia will follow suit. Pakistan, which is at the centre of a major economic crisis, for instance, may strike a deal with Russia soon for its oil needs.

Saudi Arabia raised the price of oil for Asia in the past too, but revised it down, a few weeks later, perhaps in response to flagging demand - an inevitable consequence.

In addition, the volume of imports from South Asia, especially from Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Nepal, has come down drastically due to prevailing economic troubles in respective countries.

In this context, a rise in oil price - even as a purely cosmetic measure - is hardly a catalyst for shoring up the demand from Asia, especially when there is plenty of oil at rock bottom prices elsewhere.

Against this backdrop, the perceived unity among the OPEC+ members is again under spotlight as never before. Some analysts fear that a potential, major fissure in the cartel is inevitable over the production cuts - and a few regional issues too - in the near future.