Despite the relative

rise in crude oil prices in the markets in the early hours on Wednesday, the downward

trend started continuing once again as the day wears on.

As of 10:35 GMT,

the prices of WTI and Brent were at $95.62 and $99.13 respectively.

The fall in

prices on Tuesday, perhaps, may have stemmed from two factors: the revolving optimism

over the revival of the JCPOA, 2015 Iranian nuclear deal, was back in the green

realm, after Russia’s announcement that it got the written guarantee from the

US about its trade dealing within the framework of the JCPOA being exempt from the

sanctions; in addition, the API, American Petroleum Institute, reported that

there was a significant crude build in the US during the week ending March, 15.

The EIA, US Energy

Information Administration, will release its own data of the US crude oil

inventories on Wednesday. Analysts eagerly await the report to see whether the data

from the two agencies forms a consistent pattern in the current circumstances that

breed unprecedented uncertainty in the markets.

Although the

West showed its determination to keep the Russian oil away from the

international markets, they find it hard to fill the gaping holes in the supply

chains; the major producers, meanwhile, show reluctance to increase the output,

citing various reasons ranging from contractual obligations to unrealistic

logistical challenges, something that they usually blame on the under-investment

in the sector.

Moreover,

the major producers in the Middle East, especially the UAE and Saudi Arabia,

stubbornly refuse to succumb to the American pressure, not only to boost the

production, but also to isolate Russia, a fellow OPEC+ member.

The

hastily-arranged visit by the British prime minister to the region, analysts

believe, may be an attempt to make a bridge between the former allies at a very

crucial time – especially when the Middle Eastern bigwigs refuse to lift their

phones up!

The OPEC+, meanwhile,

voiced its concern over the war in Ukraine and its political fallout: the OPEC+

says the developments intensify the global inflation that in turn hurts the oil

demand – and consumption – in addition to, of course, much-needed investment.

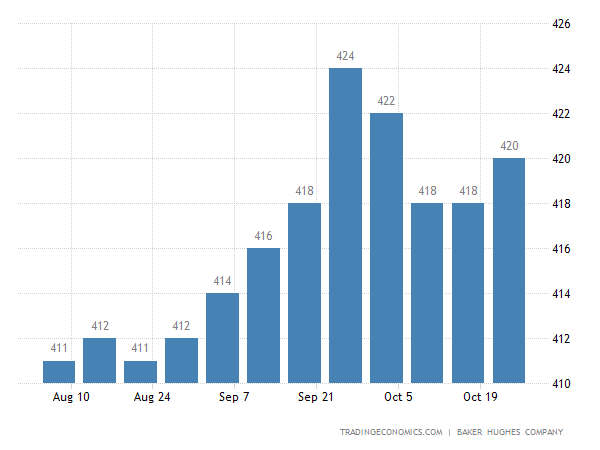

Judging by

the rig count, the US has ramped up its oil production. It, however, is enough

the bring down the prices at the pumps, according to analysts. The US needs to

import more oil in order to keep the prices low – and affordable for the

ordinary Americans.

Analysts in

the crude oil markets have been warning against the price of crude oil going

past $100 a barrel: they were in fear of demand destruction, when the price

reached 13-year high; the latest API inventory data shows it could be real if

the prices remain above $100.

It is not rocket

science to see why that is going to be the case: when prices go through the

roof, ordinary motorists just adapt their budget by consuming low and cut down

on their travels.

In short,

the price of crude oil at the current level is neither sustainable nor desirable

by anyone, including the oil producers, because the latter have been there

before and know very well what goes up comes crashing down, while causing havoc

at many different levels in the sector; what happened in 2014 is a classic case

in point.

Russia, having

been battered by the crippling sanctions in the aftermath of the war in

Ukraine, has since offered crude oil at discounted rates to what the former

considers as ‘friendly’ nations; India has already shown it enthusiasm over the

offer and is exploring ways to bypass the US dollar as the exchange currency

for the deal.

India, the

world’s third largest consumer, will certainly use its political and economic

power in the region not to bend under the pressure from the West, citing its

own interests; India still maintains its neutrality when it comes to the war in

Ukraine and shows no signs of changing it on a whim.

Even the Western

countries that warmed to the idea of sanctions against Russia, apart from

Canada, are already feeling the pinch on the economic front due to rising

energy prices.

If the real

concerns are not addressed collectively, the alliance may see cracks at the

seam much earlier than they anticipated; unlike the strong men like President Putin

and President Xi Ji Ping who are in their poistions absolutely for life, most Western leaders are elected for shorter periods

and the survival in even those periods stems from sheer luck rather than from broad-based

political strength.

In this

context, why the Western leaders run helter-skelter in seeking alternatives for

the vacuum left in the energy markets due to the expulsion of Russia is fully

understandable. How successful they are going to be in this endeavour, however,

is something that remains to be seen in the coming weeks.